I’m an ancient Asian art buff, and have been so for the last two decades. Deeply inspired by the masters of Japanese Ukiyo-e painting, I aim to convey a deeply evocative and somewhat reminiscent picture of a past both foreign and beautiful through my pieces. The appreciation for natural beauty is ever-present in ancient Ukiyo-e prints, when notions of time and enjoyment had very different connotations to those of today. The love for natural landscapes is a sentiment that strikes a chord with my own aesthetic preferences, both spiritually and artistically, and for that reason, even when I interpret sceneries from classic Ukiyo-e pieces, I tend to entirely omit any traces of artificial construction or human activity.

The way I work my pieces distances itself greatly from the traditional artform of Ukiyo-e print-making, although it does borrow concepts. The bulk of my work consists of finding Ukiyo-e in the public domain, planning which sections to replicate and collage and which colour palette to use, then sketching out the piece before moving on to digital painting and processing, for the final assemblage. Lastly I tend to spend a lot of time in post-treatment to bring out or suppress certain tones, and thus create a vintage mood. With this last step I am making an artistic statement of sorts. What I am doing is not new, it is not novelty, it has always been done, because everything is a throwback; everything is a remix.

'We stand on the shoulder of Giants' Bernard de Chartres, and later Isaac Newton

True to the spirit of remixing, my method utilizes both physical and digital mediums to achieve the end result. It is a haphazard, creative process that includes pencil, ink-work and painting, digital editing and color correction, and even photography which is then manipulated on the computer. Although my pieces are new creations, I would not consider them original works as I am in essence recontextualizing my favourite Ukiyo-e pieces – some very well known and others anonymous and underground, – and therefore I would not consider myself a part of the contemporary wave of Ukiyo-e artists, simply because my pieces are in essence collage-like reinterpretations of existing ones.

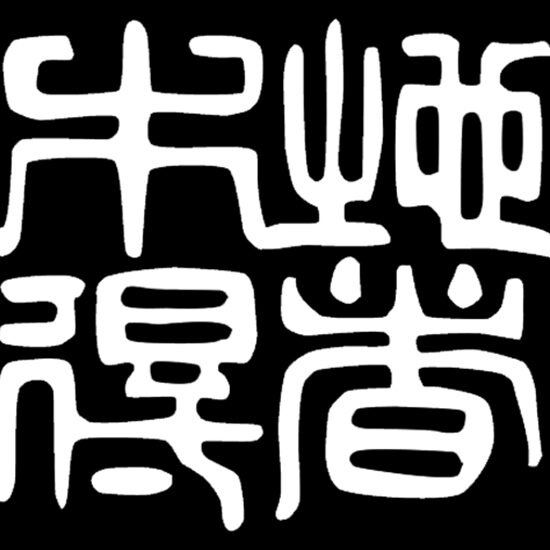

For instance, I’ll walk you through the piece above, “From the Eastern borders with Love”. It is, in its rawest form, a mashup of two ancient Ukiyo-e pieces; “Evening Snow on Fuji” by Utagawa Toyokubi II published circa 1833-4, and Utagawa Hiroshige’s “The sea shore at Izu”, published circa 1852. The focal centre of each piece has been subdued to serve a new composite image and a new contextualization has taken place, resulting in a imaginary world that was previously non-existent in any of the original pieces. Beyond the apparent juxtaposition of elements, replicated proportionally, a lot of attention was paid to colour enhancement or substitution as well as which elements to keep faithful to the originals and which portions to change without losing touch. I could of course always depart on a full reinterpretation, but part of the intended spirit behind my work is to maintain a certain liaison with the past; a dialogue so to speak.

Tendentiously my work comprises of a remix between four or five pieces, but as in the case in point above I may opt to marry as little as two pieces, or even, in rare cases, attempt to completely recontextualize one piece. It is rare that I attempt such a feat principally because masterpieces are complete worlds on their own right. They are things of beauty that need no complementing in any shape or form, and should be respected as such.

'It rocks my boat.'

Reinterpretating ancient art provides me with a freedom of expression that is not limited by genre or nomenclature, while remixing gives me a sense of connection to the past and the satisfaction of creation something new. Well, it rocks my boat, but it is not without trouble.

Seeing that my works are in essence derivative they are both loved and hated to equal proportions. Purists criticise and denounce my building on pre-existing pieces, more moderate and perhaps experimental folk identify with my perspective, and many art-lovers admire the resulting images. I make no claims and make no excuses. My hat goes off to those that appreciate what I do, and my heart to those that purchase one of my pieces. Ranting and raving is to be expected when dealing with partial reproductions and derivative versions of existing works. That is all well and good, in my humble opinion the ‘art-debate’ surrounding Ukiyo-e is both barren and fruitless. One should understand both the history and process of Ukiyo-e prints before even entering the debate. Knowing a little about copyright and fair use couldn’t hurt as well.

The rights holder, or owner of a Ukiyo-e print only holds the copyright to the reproduction he has purchased and not to the original piece, which usually cannot be reprinted again due to the destruction of the original woodblock from which it was printed. Each Ukiyo-e artwork can have hundreds of prints, all with subtle variations, and hence hundreds of owners. For this, and other reasons such as age and unknown provenance, Ukiyo-e images are by large in the public domain, and are free for anyone to use, print or distribute to their own accord (see this link for more on the history of the Japanese copyright system, or download the pdf here).

A derivative work is a work recast, transformed, or adapted from or upon one or more preexisting works. Moreover, by law, the fair use doctrine is a carve-out-to-infringement defense that is available to someone who uses another’s work—without permission—in the creation of his or her own. Works that incorporate portions of a copyrighted piece but only so much as is absolutely necessary to whatever point is being made through its use are attributed fair use. As stated above most Ukiyo-e prints are in the public domain such as those made available by the U.S. Library of Congress (see link), although each high resolution image has been provided by a donor who may have attributed certain limitations to it (more on that specific case here).

'Nothing is lost. . .Everything is transformed.' Michael Ende

Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig founded creative commons in 2001 with the intent of providing an alternative to the default exclusive copyright regime applied currently on intellectual property through which remixing is legally prevented. Acting upon the premisse that current law strangles creativity, the creative commons introduces new licenses as tools that enable remix culture to flourish in the digital age; or age of the remix as some would have it.

Remix culture when compared to the default media culture of the 20th century can be understood using computer technology terminology as Read/Write culture (RW) vs. Read Only culture (RO).

Like many enlightened minds before, Lessig understood that we all build upon past discoveries and that nothing is truly new on its own right. That life breeds on previous life. Essentially, that everything is a remix.

'good artists copy; great artists steal' Pablo Picasso, and later Steve Jobbs

To reinterpret ancient pieces from old Japanese Masters of the art-form brings me great satisfaction, and no disrespect or appropriation is intended. I am a big supporter of the ‘Remix Culture’ and I truly believe that my work is a homage to the past.

To those of you who have noticed that I am essentially transposing concepts from musical movements into my design methodology, for instance mashup and remix cultures, it is no accident. If you want to know more about my musical projects as an artist or ethnomusicologist, feel free to visit my personal website here.

Interesting links to this argument:

- “Everything is a Remix”. Documentary, 2012: link

- “What are derivative works under copyright law”. Stephanie Morrow, 2009: link

- “Remixing Culture And Why The Art Of The Mash-Up Matters”. Ben Murray / Crunch Network, 2015: link

- “Remix Culture: Rethinking What We Call Original Content”. Matt Jessel, 2013: link

- “Laws that choke Creativity”. Lawrence Lessig in Ted Talk, 2007: link